Hezekiah

| Hezekiah (Hizqiyyahu ben Ahaz) |

|

|---|---|

| King of Judah (Melekh Yehudah) |

|

King Hezekiah in a 17th century painting by an unknown artist in Sankta Maria church, Åhus, Sweden.

|

|

| Reign | coregency with Ahaz 729, sole reign 716 – 697 BC coregency with Manasseh 697 - 687 |

| Born | c.739 BC |

| Birthplace | probably Jerusalem |

| Died | c.687 BC |

| Place of death | probably Jerusalem |

| Predecessor | King Ahaz |

| Manasseh (only male child) | |

| Successor | Manasseh |

| Offspring | Manasseh |

| Royal House | House of David |

| Father | King Ahaz |

| Mother | Abijah, also called Abi |

| Kings of Judah |

|---|

|

Saul • David • Solomon • Rehoboam • Abijah • Asa • Jehoshaphat • Jehoram • Ahaziah • Athaliah • J(eh)oash • Amaziah • Uzziah/Azariah • Jotham • Ahaz • Hezekiah • Manasseh • Amon • Josiah • Jehoahaz • Jehoiakim • Jeconiah/Jehoiachin • Zedekiah |

Hezekiah is the common transliteration of a name more properly transliterated as "Ḥizkiyyahu" or "Ḥizkiyyah." (Hebrew: חִזְקִיָּ֫הוּ, חִזְקִיָּ֫ה, יְחִזְקִיָּ֫הוּ, Modern H̱izkiyyahu, H̱izkiyyah, Yeẖizkiyyahu Tiberian Ḥizqiyyā́hû, Yəḥizqiyyā́hû; Greek: Ἐζεκίας, Ezekias, in the Septuagint; Latin: Ezechias) was the son of Ahaz and the 14th king of Judah.[1] Edwin Thiele has concluded that his reign was between c. 715 and 686 BC.[2] He is also one of the kings mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew.

Hezekiah witnessed the forced resettlement of the northern Kingdom of Israel by Sargon's Assyrians in c 720 BC and was king of Judah during the invasion and siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib in 701 BC. The siege was lifted by a miraculous plague that afflicted Sennacherib's army.[3] Even so, the Assyrians conquered much of Judah, and Hezekiah's people came to yearn for an ideal king who would restore the golden age of David.[3]

Notably, Isaiah and Micah prophesied during his reign.[1] Hezekiah enacted sweeping religious reforms, during which he removed non-Yahwistic elements from the Jerusalem temple.[1]

Contents |

Etymology

Hezekiah, more properly transliterated as Ḥizkiyyahu (and sometimes as Ezekias) (Hebrew: חִזְקִיָּ֫הוּ Ḥizqiyyāhu, Khizkiyahu; or יְחִזְקִיָּ֫הוּ Yəḥizqiyyāhu, Y'khizkiyahu); ; or Ḥizkiyyah (Hebrew: חִזְקִיָּ֫ה Ḥizqiyyāh). The root of the name חִזְקִיָּהוּ Ḥizkiyyahu is חזק, a verb stem that can mean

- "strengthen", "fortify" in the pi'él (חַזֵּק),

- "hold", "seize" in the hif'il (הַחֲזֵק), and

- "gather one's strength", "take courage" in the hitpa'él (הִתְחַזֵּק).

It also spawns a number of nouns, including

- חוֹזֶק, חָזְקָה, חֶזְקָה "strength", and

- חֲזָקָה "taking hold", "seizing", "occupying", "presumption" [of entitlement]

as well as the adjectives

- חָזָק, חָזֵק "strong".

Accordingly, חִזְקִיָּהוּ Ḥizkiyyahu can be said to mean something like "Strengthened by God".[4]

The Biblical account

The main accounts of his reign are found in the Hebrew Bible, in 2 Kings 18-20, Isaiah 36-39, and 2 Chronicles 29-32.

Reign over Judah

According to the Bible Hezekiah took the throne at the age of twenty-five (2 Chronicles 29:1) and reigned for twenty-nine years (2 Kings 18:2). Some writers have proposed that Hezekiah served as coregent with his father Ahaz for about fourteen years from 729 BC. His sole reign has been dated by Albright from 715 – 687 BC or 716 – 687 BC according to Thiele, the last ten years of which were as coregent with his son Manasseh.[5]

According to the Bible Hezekiah introduced religious reform and reinstated religious traditions. He set himself to abolish idolatry from his kingdom, and among other things which he did to this end, he destroyed the "brazen serpent", which had been relocated at Jerusalem, and had become an object of idolatrous worship. (2 Kings 18:4; 2 Chronicles 29:3-36) The biblical sources portray Hezekiah as a great and good king, following the example of his great-grandfather Uzziah. The book of Kings ends the account of Hezekiah with praise. (2 Kings 18:5)

According to the work of archaeologists and philologists, the reign of Hezekiah saw a notable increase in the power of the Judean state. There were increases in literacy, in the produciton of literay works and an expansion of the population of Jerusalem where the western subburs were enclosed by the Broad Wall (Jerusalem).[6]

Family and life

Hezekiah was born in c. 739 BC, the son of King Ahaz and Abijah (2 Chronicles 29:1). Abijah was a daughter of a man named Zechariah, but he was not the prophet Zechariah. Abijah was also known as Abi. (2 Kings 18:1-2) He was married to Hephzi-bah. (2 Kings 21:1) He died in 687 BC at the age of 54 years from natural causes, and was succeeded by his son Manasseh. During the last ten years of Hezekiah's life, Manasseh was his co-regent. Manasseh was 12 years old when he became co-regent. (2 Kings 21:1)

Political moves and Assyrian invasion

Between the death of Sargon, and the succession of his son Sennacherib, Hezekiah sought to throw off his subservience to the Assyrian kings. He ceased to pay the tribute imposed on his father, and "rebelled against the king of Assyria, and served him not," but entered into a league with Egypt (Isaiah 30-31; 36:6-9). If Hezekiah expected the Egyptians to come to his aid, it did not come, and Hezekiah had to face the invasion of Judah by Sennacherib (2 Kings 18:13-16) in the 4th year of Sennacherib (701 BC).

The invasion of Judah by Sennacherib and the Assyrian army was a major and well documented historical event. Sennacherib recorded on his monumental inscription, "The Prism of Sennacherib", how in his campaign against Hezekiah ("Ha-za-qi-(i)a-ú") he took 46 cities in this campaign (column 3, line 19 of the Sennacherib prism), and besieged Jerusalem ("Ur-sa-li-im-mu") with earthworks.[7] It was during the siege of Jerusalem that the Bible says the Angel of the Lord killed 185,000 Assyrian soldiers. Herodotus (c. 484 BC – c. 425 BC) wrote of the invasion and acknowledges many Assyrian deaths, which he claims were the result of a plague of mice.[8]

Hezekiah initially paid tribute to Assyria, but then rebelled.[9] The Assyrians claimed that Sennacherib raised his siege of Jerusalem after Hezekiah acknowledged Sennacherib as his overlord and paid him tribute[10]. The Bible records that eventually Hezekiah tried to pay off Sennacherib's with three hundred talents of silver and thirty of gold in tribute, even despoiling the doors of the Temple to produce the promised amount, but, after the payment was made, Sennacherib renewed his assault on Jerusalem. (2 Kings 18:14-16)[9] Sennacherib besieged Jerusalem and sent the Rabshakeh to the walls. The Rabshakeh claimed that the Israelites should not trust Yahweh or Hezekiah, pointing to Hezekiah's righteous reforms (destroying the High Places) as a sign that the people should not trust their king. The fundamental law in Deuteronomy 12:1-32 prohibits sacrifice at every place except the temple in Jerusalem; in accordance with this law Josiah, in 621 BC, Hezekiah's great-grandson, likewise destroyed and desecrated the altars (bmoth) throughout his kingdom.[9]

Sennacherib failed to conquer Jerusalem. The Bible records that Hezekiah went to the temple and there he prayed, the first king in Judah (recorded in the Bible) to do so in about 250 years, since the time of Solomon.[9]

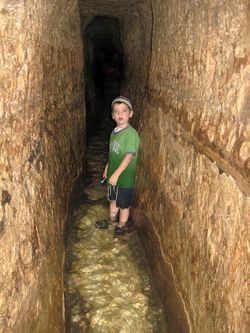

Hezekiah's construction

The Biblical account maintains that Hezekiah anticipated the Assyrian invasion and made at least two major preparations to resist conquest, construction of Hezekiah's Tunnel, also known as the Siloam Tunnel, and construction of the Broad Wall. The tunnel is 533 meters long and was dug in order to provide Jerusalem underground access to the waters of the Spring of Gihon/The Siloam Pool, which lay outside the city. This work is described in the Siloam Inscription, which has been dated to his reign on the basis of its script. At the same time a wall was built around the Pool of Siloam, into which the waters from the spring flowed (Isaiah 22:11) which was where all the spring waters were channeled. The wall surrounded the entire city, which bored up to Mount Zion. An impressive vestige of this structure is the broad wall in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem.

"When Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib had come, intent on making war against Jerusalem, he consulted with his officers and warriors about stopping the flow of the springs outside the city ... for otherwise, they thought, the King of Assyria would come and find water in abundance" (2 Chronicles 32:2-4).

The narrative in the Bible states (Isaiah 33:1; 2 Kings 18:17; 2 Chronicles 32:9; Isaiah 36) that Sennacherib besieged Jerusalem.

Death of Sennacherib

2 Kings 19:37 says -

"It came about as he was worshiping in the house of Nisroch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer killed him [Sennacherib] with the sword; and they escaped into the land of Ararat. And Esarhaddon his son became king in his place."

The Bible does not say when this took place, but Assyrian records show that Sennacherib was assassinated by his sons, Adrammelech and Sharezer, in 681 BC - i.e., twenty years after the invasion of Judah in 701 BC.[11] He was succeeded by Esarhaddon as the Assyrian king.

Hezekiah's illness and death

The narrative of Hezekiah's sickness and miraculous recovery is found in 2 Kings 20:1, 2 Chronicles 32:24, Isaiah 38:1. Various ambassadors came to congratulate him on his recovery, among them Merodach-baladan, the king of Babylon (2 Chronicles 32:23; 2 Kings 20:12). Hezekiah is also remembered for giving too much information to Baladan, king of Babylon, for which he was confronted by Isaiah the prophet (2 Kings 20:12-19). According to Jewish tradition, the victory over the Assyrians and Hezekiah's return to health happened at the same time, the first night of Passover.

Religious reforms

Hezekiah introduced substantial religious reforms. The worship of the LORD was concentrated at Jerusalem, suppressing the shrines to him that had existed till then elsewhere in Judea (2 Kings 18:22). Idolatry, which had resumed under his father's reign, was banned. Hezekiah abolished the shrines and smashed the pillars and cut down the sacred post. (2 Kings 21:3) He also smashed the bronze serpent which Moses had made, "for until that time the Israelites had been offering sacrifices to it". (2 Kings 18:4)

Hezekiah also resumed the Passover pilgrimage and the tradition of inviting the scattered tribes of Israel to take part in a Passover festival. (2 Chronicles 30:5, 10, 13, 26)

While the historicity of 2 Chronicles 30 has been questioned [12], recovery of LMLK seals from the northwest territory of Israel (corresponding to 2 Chronicles 30:11) may indicate that some sort of administrative relationship existed between Hezekiah and a minority of northern Israelites.[13].

Hezekiah's reforms removed polytheism and restored monotheism.

The books of Kings and Chronicles have lengthy passages attesting that there was effective centralization before Hezekiah - for example, in the days of David (1 Chronicles 6:31-49; 15:3-16:6; 16:37,38; 23:2-26:32) and Solomon (1 Kings 4:1-19; 6:1-7:51; 8:1-66; 2 Chronicles 2:1-7, 10).

There is also evidence from archaeology that Hezekiah did not centralize the religion in Jerusalem. He allowed, and indeed built temples at Lachish and Arad, and allowed a high place to continue in operation at Beersheva. The reference in 2 Kings 18:4 that Hezekiah "removed the high places (bamot), and broke down the pillars (massebot) and cut down the sacred poles (asherah)," is dismissed by William G. Dever [14] to be "simply Deuteronomistic propaganda". Dever and others argue that in order to establish the sanctity of their view, the P Source writers had to show it was anchored in the actions of Hezekiah.

Archaeological evidence

A lintel inscription, found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to his comptroller Shebna.

Seals

Two distinct classes of seal impressions have been found in modern Israel relating to King Hezekiah:

- LMLK seals on storage jar handles, excavated from strata formed by Sennacherib's destruction as well as immediately above that layer suggesting they were used throughout his 29-year reign (Grena, 2004, p. 338)

- Bullae from sealed documents, some that may have belonged to Hezekiah himself (Grena, 2004, p. 26, Figs. 9 and 10) while others name his servants (ah-vah-deem in Hebrew, ayin-bet-dalet-yod-mem), all from the antiquities market and subject to authentication disputes (see Biblical archaeology)

Siloam Inscription

In the Siloam Tunnel we find the Siloam Inscription, which commemorates the meeting of the two teams.

Chronological notes

There has been considerable academic debate about the actual dates of reigns of the Israelite kings. Scholars have endeavored to synchronize the chronology of events referred to in the Bible with those derived from other external sources. In the case of Hezekiah, scholars have noted that the apparent inconsistencies are resolved by accepting the evidence that Hezekiah, like his predecessors for four generations in the kings of Judah, had a coregency with his father, and this coregency began in 729 BC.

As an example of the reasoning that finds inconsistencies in calculations when coregencies are a priori ruled out, 2 Kings 18:10 dates the fall of Samaria (the Northern Kingdom) to the 6th year of Hezekiah's reign. William F. Albright has dated the fall of the Kingdom of Israel to 721 BC, while E. R. Thiele calculates the date as 723 BC.[15] If Abright's or Thiele's dating are correct, then Hezekiah's reign would begin in either 729 or 727 BC. On the other hand, 18:13 states that Sennacherib invaded Judah in the 14th year of Hezekiah's reign. Dating based on Assyrian records date this invasion to 701 BC, and Hezekiah's reign would therefore begin in 716/715 BC.[16] This dating would be confirmed by the account of Hezekiah's illness in chapter 20, which immediately follows Sennacherib's departure (2 Kings 20). This would date his illness to Hezekiah's 14th year, which is confirmed by Isaiah's statement (2 Kings 18:5) that he will live fifteen more years (29-15=14). As shown below, these problems are all addressed by scholars who make reference to the ancient Near Eastern practice of coregency.

Following the approach of Wellhausen, another set of calculations shows it is probable that Hezekiah did not ascend the throne before 722 BC. By Albright's calculations, Jehu's initial year is 842 BC; and between it and Samaria's destruction the Books of Kings give the total number of the years the kings of Israel ruled as 143 7/12, while for the kings of Judah the number is 165. This discrepancy, amounting in the case of Judah to 45 years (165-120), has been accounted for in various ways; but every one of those theories must allow that Hezekiah's first six years fell before 722 BC. (That Hezekiah began to reign before 722 BC, however, is entirely consistent with the principle that the Ahaz/Hezekiah coregency began in 729 BC.) Nor is it clearly known how old Hezekiah was when called to the throne, although 2 Kings 18:2 states he was twenty-five years of age. His father died at the age of thirty-six (2 Kings 16:2); it is not likely that Ahaz at the age of eleven should have had a son. Hezekiah's own son Manasseh ascended the throne twenty-nine years later, at the age of twelve. This places his birth in the seventeenth year of his father's reign, or gives Hezekiah's age as forty-two, if he was twenty-five at his ascension. It is more probable that Ahaz was twenty-one or twenty-five when Hezekiah was born (and suggesting an error in the text), and that the latter was thirty-two at the birth of his son and successor, Manasseh.

Since Albright and Friedman, several scholars have explained these dating problems on the basis of a coregency between Hezekiah and his father Ahaz between 729 and 716/715 BC. Assyriologists and Egyptologists recognize that coregency was a practice both in Assyria and Egypt,[17][18] After noting that coregencies were only used sporadically in the northern kingdom (Israel), Nadav Na'aman writes,

In the kingdom of Judah, on the other hand, the nomination of a co-regent was the common procedure, beginning from David who, before his death, elevated his son Solomon to the throne…When taking into account the permanent nature of the co-regency in Judah from the time of Joash, one may dare to conclude that dating the co-regencies accurately is indeed the key for solving the problems of biblical chronology in the eighth century B.C."[19]

Among the numerous scholars who have recognized the coregency between Ahaz and Hezekiah are Kenneth Kitchen in his various writings,[20] Leslie McFall,[21] and Jack Finegan.[22] McFall, in his 1991 article, argues that if 729 BC (that is, the Judean regnal year beginning in Tishri of 729) is taken as the start of the Ahaz/Hezekiah coregency, and 716/715 BC as the date of the death of Ahaz, then all the extensive chronological data for Hezekiah and his contemporaries in the late eighth century BC are in harmony. Further, McFall found that no textual emendations are required among the numerous dates, reign lengths, and synchronisms given in the Bible for this period.[23] In contrast, those who do not accept the Ancient Near Eastern principle of coregencies require multiple emendations of the Scriptural text, and there is no general agreement on which texts should be emended, nor is there any consensus among these scholars on the resultant chronology for the eighth century BC. This is in contrast with the general consensus among those who accept the biblical and near Eastern practice of coregencies that Hezekiah was installed as coregent with his father Ahaz in 729 BC, and the synchronisms of 2 Kings 18 must be measured from that date, whereas the synchronisms to Sennacherib are measured from the sole reign starting in 716/715 BC. The two synchronisms to Hoshea of Israel in 2 Kings 18 are then in exact agreement with the dates of Hoshea's reign that can be determined from Assyrian sources, as is the date of Samaria's fall as stated in 2 Kings 18:10. An analogous situation of two ways of measurement, both equally valid, is encountered in the dates given for Jehoram of Israel, whose first year is synchronized to the 18th year of the sole reign of Jehoshaphat of Judah in 2 Kings 3:1 (853/852 BC), but his reign is also reckoned according to another method as starting in the second year of the coregency of Jehoshaphat and his son Jehoram of Judah (2 Kings 1:17); both methods refer to the same calendrical year.

Scholars who accept the principle of coregencies note that abundant evidence for their use is found in the biblical material itself.[24] The agreement of scholarship built on these principles with both biblical and secular texts was such that the Thiele/McFall chronology was accepted as the best chronology for the kingdom period in Jack Finegan's encyclopedic Handbook of Biblical Chronology.[25]

|

Hezekiah of Judah

House of David

|

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ahaz |

King of Judah Coregent: 729-716 BC Sole reign: 716 – 687 BC |

Succeeded by Manasseh |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "Glossary" p. 367-432

- ↑ Edwin Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257, 217.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Hezekiah." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 12 Nov. 2009 Read online

- ↑ http://messiahtruth.yuku.com/sreply/39873/t/-truth---claim----Jews--Jesus-wrote-----claim--Jesus---Messi.html Professor Mordochai ben Tzyyion, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel

- ↑ See William F. Albright for the former and for the latter Edwin R. Thiele's, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (3rd ed.; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983) 217. But Gershon Galil dates his reign to 697–642 BC.

- ↑ David M. Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 164.

- ↑ James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965) 287-288.

- ↑ (19:35) Herodotus (Histories 2:141)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Peter J. Leithart, 1 & 2 Kings, Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible, p255-256, Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, MI (2006)

- ↑ Sennacherib's Hexagonal Prism

- ↑ J. D. Douglas, ed., New Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1965) 1160.

- ↑ Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed. Free Press, New York, 2001, ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ↑ See An Administrative Center of the Iron Age in Nahal Tut by Amir Gorzalczany.

- ↑ Dever, William G. (2005) "Did God have a wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel" (Eerdmans)

- ↑ Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (3rd ed.; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983) pp. 134, 217.

- ↑ Leslie McFall, “A Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles,” Bibliotheca Sacra 148 (1991) p. 33. (Link)

- ↑ William J. Murnane, Ancient Egyptian Coregencies (Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 1977).

- ↑ J. D. Douglas, ed., New Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1965) p. 1160.

- ↑ Nadav Na'aman, "Historical and Chronological Notes on the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the Eighth Century B.C." Vetus Testamentum 36 (1986) p. 91.

- ↑ See Kitchen's chronology in New Bible Dictionary p. 220.

- ↑ Leslie McFall, "Translation Guide" p.42.

- ↑ Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (rev. ed.; Peabody MA: Hendrickson, 1998) p. 246.

- ↑ Leslie McFall, "Translation Guide" pp. 4-45 (Link).

- ↑ Thiele, Mysterious Numbers chapter 3, "Coregencies and Rival Reigns."

- ↑ Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology p. 246.

Resources

- Grena, G.M. (2004). LMLK—A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1. Redondo Beach, California: 4000 Years of Writing History. ISBN 0-9748786-0-X.

- Austin, Lynn. Gods And Kings. ISBN 0-7642-2989-3. a fictionalized account of Hezekiah's rise to power, Book 1 in Austin's "Chronicles of the Kings" series

External links

- "Hezekiah." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- King Hezekiah from Jerusalem Mosaic

- Hezekiah See all Bible verses pertaining to King Hezekiah

- The Reign Of Hezekiah by John F. Brug

"Ezechias". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Ezechias". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Sennacherib's Invasion of Hezekiah's Judah in 701 BC - by Craig C. Broyles

- Interactive Map of Sennacherib's Invasion of Hezekiah's Judah, including the accounts of Sennacherib, Herodotus, 2 Kings, Isaiah and Micah

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||